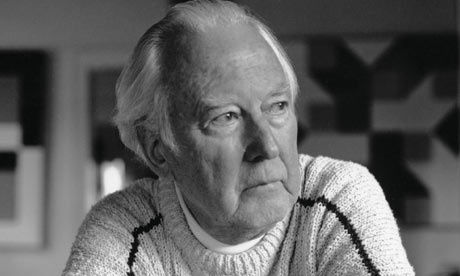

Frederick Hammersley US, 1919-2009

"My painting begins with a hunch, no plan, no theory, just a feeling to make a shape."

- Frederick Hammersley

Hammersley’s experimentation developed into the first of three series that would define his career: his “hunch” paintings. The evolution of a hunch painting began as a shape. Then he intuitively chose a color, after which he would continue adding shapes and colors by “feeling” or “hunch” and leading to finished works that may suggest a subject but remain abstract as a whole. His second series began in the late 1950s and early 1960s when he began creating geometric, hard-edge paintings. Unlike his hunch paintings, Hammersley’s geometric works were thoughtfully planned out in sketchbooks. He planned out the composition and then painted them on the canvas with a palette knife; unlike many of his contemporaries, he never used tape to create hard edges. Hammersley applied equal thought and consideration to the titles of his paintings and kept copious stream-of-consciousness notes full of puns, double entendres, and witty plays on words that would provide the viewer with some verbal insight into his abstract creations.

It was Hammersley’s inclusion in the landmark exhibition Four Abstract Classicists in 1959 alongside Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, and John McLaughlin that gained him critical recognition and cemented his place in art history. Organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and curated by critic Jules Langsner, the exhibition helped to put West Coast abstraction on the map and is also credited as the source for the term “hard-edge painting”, used by Langsner to describe the artists’ sharp-edged geometricized works.

Hammersley’s third and final series of paintings, his “organics,” began to develop around 1963-64 while he was still exploring geometry. This first phase of an organic painting consisted, as the name suggests, of entirely organic shapes hand-drawn on chipboard and painted in flat colors. After briefly working in this style, he went on to experiment with drawings, collage, prints, mosaics, photography and even computer-generated drawings. He returned to painting again in the 1970s and 80s, further developing his organics into smaller, more tactile works, each mounted in a unique frame made by the artist himself. Ever-present, of course, was his dedication to abstraction and his creative use of titles to provide a window into each individual piece.

Hammersley continued to work and create up until the day before his death. He left behind not just an impressive legacy as an artist, but also as an educator, having taught at Pomona College (1953–62), Pasadena Art Museum (1956–61), Chouinard (1964–68), and University of New Mexico (1968–71). His work was exhibited widely during his lifetime and can be found in many prominent collections including the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Huntington, the Oakland Museum, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Additionally, much of his prolific archival materials, including the artist's meticulous documentation of his painting process and materials, have been distributed by the Frederick Hammersley Foundation to several institutions, including the Archives of American Art, the Getty Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Albuquerque Museum, providing the public an opportunity to better understand the life and work of this vibrant and important artist.