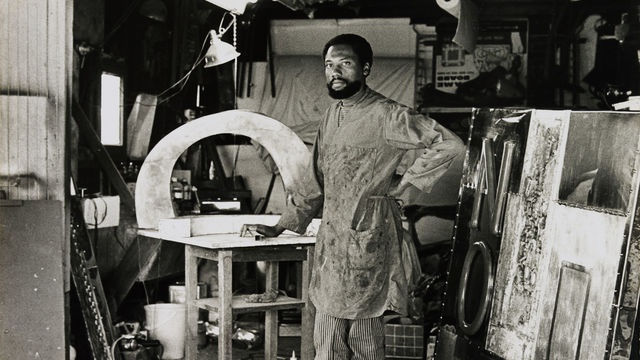

John Wilfred Outterbridge US, 1933-2020

"The process that we activate as practicing artists, as writers, as dancers, as painters, as creative people, has a great deal to do with looking for life's integrity—not what we have been but what we could be."

- John Wilfred Outterbridge

John Outterbridge has spent more than eight decades noticing, saving, and recombining parts of his surroundings. It’s an artistic method. His sculptures bring together different found materials, and the resulting assemblage turns what might seem like random detritus into a concentrated aesthetic experience. But it’s also a philosophy. “At its root,” Outterbridge explained recently in an email interview, “is the idea that everything has value. Everything has meaning. Everything has impact.”

Outterbridge was born in 1933 in Greenville, North Carolina, where he saw and felt the effects of segregation and took in from his mother the need to “press on” despite racist oppression. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1963, two years before the Watts Riots. Assemblage was part of that moment. For African-American artists, a practice that made profound meaning from what society had cast off was part of a general demand for recognition of underserved communities and unrecognized histories. Assemblage has a varied history—back to Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, at least, and including Robert Rauschenberg’s combines, Joseph Cornell’s boxes, and Edward Kienholz’s installations.

Outterbridge is part of a prominent group of black artists—including Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, John Riddle and Senga Nengudi—who nurtured their careers in Los Angeles and remained interconnected as they rose to prominence. They brought a modernist genre into conversation with African-American heritage, which Angelenos were reminded of in Now Dig This!, a group show of L.A. black artists active in the 1960s and 70s presented at the Hammer and part of 2012’s Pacific Standard Time, a multi-venue exploration of Los Angeles’ art scene.

Like several in that set, Outterbridge took his creative practice into arts education and organization as well as art-making. Centering these efforts in the South Los Angeles region, he co-founded the Compton Communicative Arts Academy in 1969. He was later director of the Watts Towers Art Center, housed next to Simon Rodia’s iconic Watts Towers—a mosaiced monument meticulously embellished with salvaged shells, tile, and glass—and co-founded by Purifoy after the Watts Riots. Outterbridge worked there for 17 years. He lived the belief that “art has a social role and can actually change society.” Outterbridge’s assemblage is uniquely suited to this kind of change—since it is open to and valuing all. “Wherever I was,” he said, “anything was available and anything could be used and was used.”

It was a lesson that connected the evolving conditions of L.A. with Outterbridge’s earliest experiences. He learned as a boy the beauty of folk art and the aesthetic wisdom of everyday practices. “The rags that hung out to dry blew in the wind like colorful tapestries,” he remembered, “and I was touched by the perfect order that those rags had.” He treasured ad-hoc assemblage in his neighborhood like “the glass bottles in the trees that made music for me and my siblings.”